17.01.2023: The New Option Parser#

Note

The new option parser is not merged yet and subject to change. I'll write this as if it had been merged already, so we can keep the article once it is.

Note

We plan to continue working on the option parser, so this article might be outdated by the time you read it. We may update it, if there are major changes, but since this is a blog the main goal is to describe the current state at the time of writing.

We reimplemented our option parser from scratch for a couple of reasons. One goal was to make it more robust to to certain kinds of errors, for example, the old parser allowed specifications that were not valid and silently ignored errors caused by this. The main issue, however, was that parsing and construction of objects was integrated in the old parser: defining an option immediately parsed it. This meant that all parsing and construction had to happen at the same time. The problem with that was that we had no control over the lifetime of the objects and reusing objects was tricky. For example, in the future, we want to be able to define a heuristic, and then use this heuristic in two different searches. If possible, only one heuristic object should be constructed and used in both searches. We have an idea of how to achieve this by having the option parser construct "Builders" that can be shared and construct objects when necessary but can reuse previously constructed objects where possible. The old option parser did not fit this model and since there were other things we didn't like about it, we started from scratch.

Features#

The parser should not be planning-specific and should be easily usable in other

projects. It consists of two namespaces plugins and parser that only depend

on the namespace utils and each other (specifically, parser depends on

plugins). The general idea is that it can parse expressions like this

let(x, f1(), f2(x, x, k = [1, 2, 3.5]))

This example would construct an object for f1 with no parameters, store it in

a variable x, construct a list of three floating point numbers

[1, 2, 3.5], and finally construct an object for f2 that uses x as both the

first and second parameter and the constructed list as a key-word argument with

key k.

What object will be constructed for f1 and f2? What parameters are allowed

or required? How do we know that parameter k requires a list of floats? All

of this is defined in Features. A feature also can contain documentation

which we use to automatically generate the documentation in this wiki.

Let's look at an example for the h^m heuristic:

class HMHeuristicFeature : public plugins::TypedFeature<Evaluator, HMHeuristic> {

public:

HMHeuristicFeature() : TypedFeature("hm") {

document_title("h^m heuristic");

add_option<int>("m", "subset size", "2", plugins::Bounds("1", "infinity"));

Heuristic::add_options_to_feature(*this);

document_language_support("action costs", "supported");

document_language_support("conditional effects", "ignored");

document_language_support("axioms", "ignored");

document_property(

"admissible",

"yes for tasks without conditional effects or axioms");

document_property(

"consistent",

"yes for tasks without conditional effects or axioms");

document_property(

"safe",

"yes for tasks without conditional effects or axioms");

document_property("preferred operators", "no");

}

};

The feature HMHeuristicFeature derives from plugins::TypedFeature<Evaluator,

HMHeuristic> which tells the system what kind of object is created (a

HMHeuristic). Every feature also has a category, in this case Evaluator,

which is used for type checks. For example, our search algorithms expect an

Evaluator, not specifically a HMHeuristic.

The base constructor is called with the key hm, which will tell the parser

that a string like hm(...) should be parsed with this feature.

In the constructor, we then see multiple lines defining options and adding documentation that you can find reflected in the Evaluator documentation.

Plugins#

So far, the feature in the example above and its category Evaluator are

unknown to the parser and we have to register them in some way.

Here, we wanted to avoid an implementation with one central code file

that registers everything. Instead, we keep the feature definition

together with the implementation of the feature. To register a feature,

we define a static plugin for it.

For example, to register the category Evaluator, we use a

TypedCategoryPlugin

static class EvaluatorCategoryPlugin : public plugins::TypedCategoryPlugin<Evaluator> {

public:

EvaluatorCategoryPlugin() : TypedCategoryPlugin("Evaluator") {

document_synopsis("...");

allow_variable_binding();

}

}

_category_plugin;

A category plugin defines the base class of objects from this category as

a template parameter ( Evaluator, in this case) and a user-friendly name in

the base constructor ("Evaluator"). The constructor can then add documentation.

The category for Evaluator also allows users to define variables with the

"let" syntax mentioned above. In the future, we plan to make this possible for

all features but this requires more thought.

Given that the code now knows about evaluators, we can also register our feature for the h^m heuristic. We also do so with a plugin:

There are two additional kinds of plugins: a SubcategoryPlugin defines

a subsection in the documentation. When defining a feature, we

can associate it not only with a category but also with a subcategory.

This is used to group some features, say all PDB heuristics, within the

documentation of their category. Subcategories mainly consist of a key

(used to sort and access them) and a human-readable title. Every feature

not associated with a subcategory will be shown outside of the

subcategories. (See evaluator

documentation for an example).

static class PDBGroupPlugin : public plugins::SubcategoryPlugin {

public:

PDBGroupPlugin() : SubcategoryPlugin("heuristics_pdb") {

document_title("Pattern Database Heuristics");

}

}

_subcategory_plugin;

The final kind of plugin is a TypedEnumPlugin. It defines enum values

together with their documentation. After defining a TypedEnumPlugin for an

Enum, we can define options of that enum type in features and

will get type checks and appropriate documentation for them.

static plugins::TypedEnumPlugin<LPSolverType> _enum_plugin({

{"clp", "default LP solver shipped with the COIN library"},

{"cplex", "commercial solver by IBM"},

{"gurobi", "commercial solver"},

{"soplex", "open source solver by ZIB"}

});

Note that in the old parser, we had a special method add_enum_option, while

we now can treat the option like any other option:

feature.add_option<LPSolverType>(

"lpsolver",

"external solver that should be used to solve linear programs",

"cplex");

Registries#

Plugins are defined as static objects but in C++ there is no guarantee

that static objects are constructed in a certain order. It could thus happen

that we define an option of category T before saying that category T even

exists. We thus first collect all features in in a preliminary registry without

any checks (the RawRegistry) and then, after the program started running,

create the final Registry from the RawRegistry. At this point we perform

all necessary checks, for example, that all options of all features come from

a known category, that no two features or categories share the same key, and so

on.

In addition to the RawRegistry and the Registry, there is the

TypeRegistry, that stores information on and documents all types that can be

used in option strings. Type classes let us handle such types as first-class

citizen and define conversions between them. Examples are BasicType (int,

double, bool), FeatureType (those defined by a category plugin), ListType

(for list options), and EnumType (defined by an enum plugin). Two more

unusual types are EmptyListType (our lists are typed but an empty list is

special, because it doesn't fix the nested type) and SymbolType (for example

a string representing an enum value).

Parsing Option Strings#

We parse option strings in 4 steps:

- We split the string into tokens

- We create an abstract syntax tree (AST) from the token string

- We decorate the AST with information about the registered features

- We recursively construct objects from the decorated AST

In the following, we go through an example, of how a simple option

string would be parsed. We use the features defined above and a

(fictitious) search algorithm astar that takes two parameters: eval of

category Evaluator and an enum option lpsolver of category LPSolverType

(the real A* search does not use an LP solver and takes other options

which we ignore here).

The option string, we want to parse is

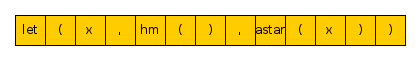

The first step is to split it into tokens. We distinguish the following tokens:

- opening and closing parenthesis: ()

- opening and closing bracket: []

- comma: ,

- equals: =

- integer: 1, 2k, 4m, 5g, -6, infinity (parsed as max int)

- float: 1.2, 3e-4, 5.6k

- bool: true, false

- let: let

- identifier: hm, astar, ... (any string of word characters, beginning with a letter or underscore, except the reserved "let")

In our example, splitting the string results in the following list of tokens.

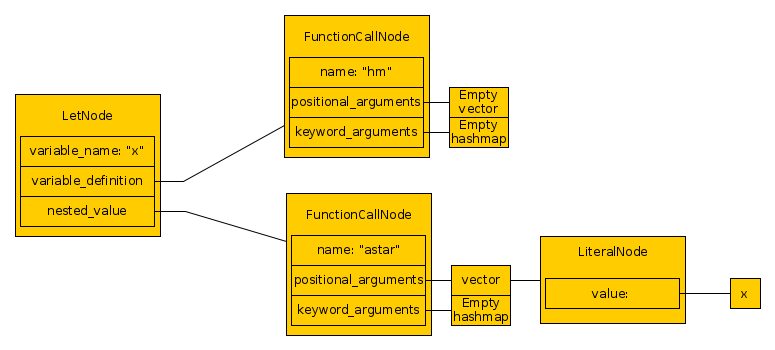

Next we create the AST from that list of tokens. This interprets the options syntactically, without considering the registered features yet. For example, since the token stream starts with a let token, we know that this is a variable definition, but we don't know the type of the variable at this point.

Token sequences like

hm() or astar(x) are interpreted as function calls, where a named

function (in this case hm and astar) is called with some positional and

some keyword arguments. Think of a function call in Python.

The resulting AST for our case is

The top-level node is a let-node (a variable definition) that defines

variable x with a function call to a function hm without any positional or

keyword arguments. This variable definition is then used in an another function

call node to a function astar, with a single positional argument that is

a literal x. (At this point, we do not yet know whether x is a variable or,

say, and enum value.)

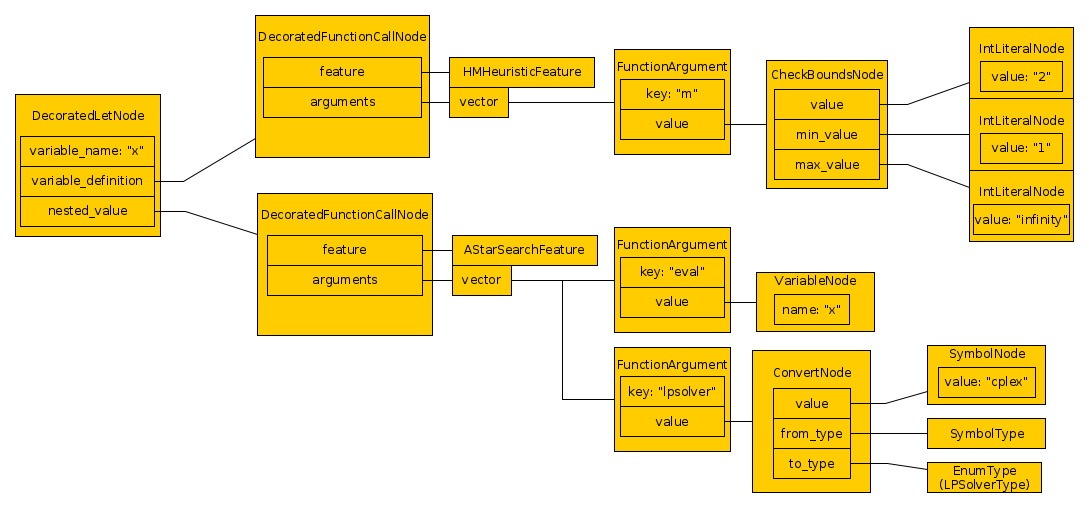

Next, we decorate the AST by adding information about the registered

features. In function call nodes, we look up the corresponding feature

to figure out which arguments the positional arguments refer to, check

that keyword arguments refer to actual options, add default values, and

check that all mandatory options are specified. For example hm has an int

option m with a default value of 2, so we parse and decorate this default

value and use it instead of a user-specified value. This option also has bounds

to check that the value of m is positive. These bounds cannot be checked yet,

as the actual value is not constructed yet, but we include a node in the

decorated AST to check the bounds before using them. When decorating the

subtree of astar, we realize that x is the name of a variable and is the

value of the option eval, while there is an unspecified option lpsolver

that takes its default value of cplex. In contrast to x, the value cplex

is interpreted as a symbol, and we know that during construction, we have to

convert this value to the correct enum type. ConvertNodes like this are also

used to convert integers to floats (in case the user used an integer for an

option that should be float), or lists to the appropriate type. This can be

tricky: for example, the string [[], [23, 3k]] can be converted to list of

list of floats, even though it represents a list where the first entry is an

empty list (that doesn't specify an element type), while the second element is

a list of integers. While decorating, we add the necessary ConvertNodes.

The decorated AST is

Finally, the objects in the decorated AST can be constructed. We do so

in a recursive way, always returning constructed values wrapped in the Any

type that can contain values of any type. For example, constructing the

IntLiteralNode with value "2" returns and Any containing the int 2.

"Constructing" the CheckBoundsNode consists of constructing its arguments,

checking if the bounds are satisfied and then returning the constructed

value. Similarly, "constructing" a ConvertNode consists of performing the

transformation and returning the transformed value. FunctionCallNodes

are constructed by first constructing all their arguments and storing

them in an Options object. This can be thought of as a hash map mapping names

of options to Any values representing the parsed and constructed arguments.

The DecoratedLetNode first constructs its variable definition, then stores

the constructed value in a context that is accessed during the construction of

VariableNodes. They then just return the already constructed objects. This

ensures that if a variable is used multiple times within its scope, all users

use the same value.

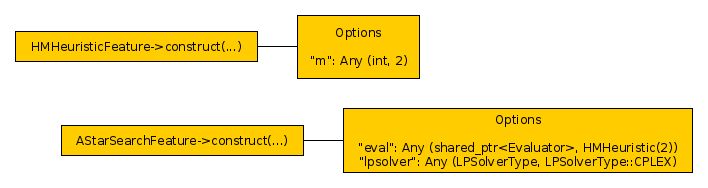

In our example, we thus construct two objects. First the h^m heuristic, then the search. Each of them gets an options object with the necessary parameters.

The feature classes HMHeuristicFeature and AStarSearchFeature determine how

the final objects are constructed. We derived HMHeuristicFeature from

plugins::TypedFeature<Evaluator, HMHeuristic> which adds a default

implementation for the construction: it calls the constructor of HMHeuristic

that takes a single Options object as its parameter and returns a shared

pointer to the constructed object. If such a constructor does not exist, or if

additional checks have to be performed during the construction, the function

Feature::create_component can be overridden.